Why is laughter important?

Laughter gives us the feel-good factor – creating laughter creates enjoyment and relaxation, which will make us teach better and our students learn better.

Laughter can be very memorable – a class which included hilarity will be remembered long after other, more sedate lessons, have been forgotten, while a mistake which raised a giggle will be carefully avoided in future.

Laughter can help break the ice – this is especially important for new classes, particularly if the students are from very different cultures or age groups, and may find it intimidating to start talking to each other and getting to know each other. Ice-breaking can also be useful for difficult topics which people may feel awkward about discussing. Laughter, used skilfully, can help open up a controversial topic and make it safer to talk about.

It doesn’t have to be a new class or a difficult topic for laughter to be useful as a warmer. It gets people talking, makes people curious about the topic, and helps people see new and interesting connections.

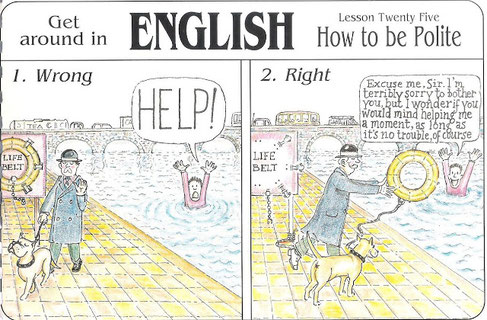

In a supportive classroom environment, laughter can help reduce embarrassment. A lot of students are very hesitant about practising pronunciation in front of others – but the teacher modelling an exaggerated pronunciation, and allowing themselves to be laughed at, can release tension and open the way to lowered inhibitions and greater confidence.

Laughter may be a useful way for teachers to enforce discipline without causing students to lose face and creating conflict. It needs to be done sensitively, with the right students, but a humorously raised eyebrow or a gentle class joke about a repeat chewing gum offender can be less aggressive and more productive than a telling-off.

Finally, laughter is also useful for the actual content of our lessons: trying to understand something funny in another language can reveal all sorts of cultural assumptions, or encourage students to dig deeper into the multiple meanings of words and their nuances, all of which helps students get a fuller understanding of English as a language.

How can we create or encourage laughter in our lessons?

As already mentioned, something humorous like a funny picture or a short video involving visual humour, can be a good way to start a lesson, generate interest in the topic, and get everyone in a positive frame of mind.

Latecomers, coffee drinkers, or gum chewers (especially if they are repeat offenders) can be given some gentle teasing.

For new classes, asking them to tell each other funny stories can be a good getting-to-know-you activity.

Collect cartoons and internet memes that are funny and will help students remember important language points. Print them out and display them on the classroom walls.

Before a debate, show students a funny video or cartoon on the topic of the debate. Ask them to predict the topic and identify key areas of controversy.

For reading or listening texts, you could choose something that has a humorous tone (or at least one humorous comment) and ask students to identify it. Or get them to look out for humour in coursebook texts – often the magazine articles on which coursebook readings are based have a slight undertone of humour, or include jokey asides. Identifying this tone is a very useful skill for language learners, in order to judge the overall message and implications of a piece.

On the topic of news, try parody news websites like Newsthump (maybe select individual headlines or extracts rather than the whole article)

As a break during an intense lesson (maybe during a long reading or a rather dry academic topic), ask students to tell each other the funniest thing that has happened to them recently. (Or describe a funny advert they like, a funny person they know …)

For grammar practice, try to gather a collection of jokes that use the grammar point you are teaching. Give each student one joke and ask them to memorise it. Then get them to mingle, telling each other their jokes, and finally vote on the funniest joke.

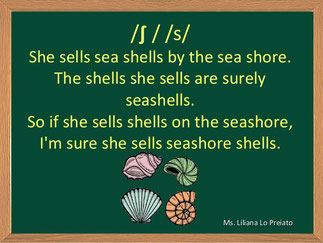

Jokes can also help raise awareness of spelling and pronunciation: find jokes that are based on puns, and then get students to identify the double meaning that creates the humour. Follow-up by investigating varying spelling patterns of particular sounds.

Before pronunciation work, help students to lose their inhibitions by asking them to make funny faces and sounds at each other. You can also drill over-exaggerated intonation, or ask students to speak in a very over-the-top British accent (ironically, this often sounds more natural than their normal accent). It is often important for the teacher to lead the way in this kind of activity, otherwise students will be very reluctant to get involved.

Tongue-twisters are a great source of laughter, and good pronunciation practice at the same time.

In a speaking activity like a role-play or an anecdote, encourage students to include an element of humour. If the students perform their role-plays at the end of the lesson, ask the listeners to choose which was the funniest.

As a follow-up to a vocabulary lesson, ask students to create funny internet memes using the vocabulary they have learnt.

In monitoring a speaking activity, make sure you note down any mistakes that made you giggle. Put them up on the board afterwards (anonymously) and ask students to discuss why a native speaker might laugh if you made this mistake.

When can laughter be counter-productive?

If students feel humiliated: make sure that any teasing is good-natured. It’s probably best to only use teasing as a discipline method for students you know fairly well, and particularly for repeat offenders. Monitor anecdote activities to check that students don’t tell anecdotes that poke fun at another student. Model silly pronunciation activities yourself so students don’t feel so self-conscious. Don’t force a student to perform a funny role-play if they are obviously uncomfortable doing so.

If students don’t understand the joke and feel left out: be prepared to explain jokes if necessary. Remind students that humour is difficult to understand in a different language and you don’t expect them to understand every joke (this is especially important for some types of humour such as a satirical article). Traditional jokes based on puns are incomprehensible to many nationalities – part of what makes them funny is our expectation of a pun. It may also be worth explaining to students that these jokes are unlikely to raise more than a groan or a wry smile, even among native speakers.

If students are offended by a joke: Humour is a good way to defuse a hot topic, but it can also be a good way to get a few people very angry! If you plan to use a potentially offensive joke, think about how to deal with this. Perhaps present the joke, and ask students: “Do you find this joke offensive?” “Do people tell this kind of joke in your country?” “If someone told this joke, would you laugh, say nothing, or confront them?” If you inadvertently offend a student with a joke, of course you will need to sit down, talk about it, make sure that you understand why they are upset, and apologise.

If students feel that the lesson isn’t serious enough: The best response to this is probably to get students to provide a rationale for the activities you’ve chosen to do. (Make sure that you have a rationale for them!) You might like to elicit from them the benefits of humour discussed above.

In General:

Don't be afraid of laughter in your classroom, but think about how you might include more of it, both to benefit your students' learning and to help you reduce stress and stay sane. Although some types of jokes can be risky, and you may need to be prepared to deal with problems that arise, there are all sorts of situations where humour is easy to incorporate and can lift a lesson from enjoyable and useful to entertaining and memorable.

Write a comment